|

|

|

ORIGINAL ARTICLE |

|

|

|

| Year : 2013 | Volume

: 19

| Issue : 4 | Page : 454-458 |

| |

The proportion of tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency and PAH gene deficiency variants among cases with hyperphenyalaninemia in Western Iran

Keyvan Moradi1, Reza Alibakhshi2, Shohreh Khatami3

1 Department of Genetics, Faculty of Science, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran

2 Department of Biochemistry, School of Medicine; Nano Drug Delivery Research Centre, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

3 Department of Biochemistry, Pasteur Institute of Iran, Tehran, Iran

| Date of Web Publication | 4-Jan-2014 |

Correspondence Address:

Reza Alibakhshi

Department of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah

Iran

Source of Support: This study was supported by a grant from Kermanshah

University of Medical Sciences. The Vice Chancellor for Research at

Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences in Iran has provided a grant to

support this study, Conflict of Interest: None

DOI: 10.4103/0971-6866.124375

Abstract Abstract | | |

Background: Defects either in phenylalanine hydroxylase (PheOH) or in the production and recycling of its cofactor (tetrahydrobiopterin [BH4]) are the causes of primary hyperphenylalaninemia (HPA). The aim of our study was to investigate the current status of different variants of HPA Kurdish patients in Kermanshah province, Iran.

Materials and Methods: From 33 cases enrolled in our study, 32 were identified as HPA patients. Reassessing of pre-treatment phenylalanine concentrations and the analysis of urinary pterins was done by high-performance liquid chromatography method.

Results: A total of 30 patients showed PAH deficiency and two patients were diagnosed with BH4 deficiency (BH4/HPA ratio = 6.25%). Both of these two BH4-deficient patients were assigned to severe variant of dihydropteridine reductase (DHPR) deficiency. More than 75% of patients with PAH deficiency classified as classic phenylketonuria (PKU) according their levels of pre-treatment phenylalanine concentrations.

Conclusion: Based on the performed study, we think that the frequency of milder forms of PKU is higher than those was estimated before and/or our findings here. Furthermore, the frequency of DHPR deficiency seems to be relatively high in our province. Since the clinical symptoms of DHPR deficiency are confusingly similar to that of classic PKU and its prognosis are much worse than classical PKU and cannot be solely treated with the PKU regime, our pilot study support that it is crucial to set up screening for BH4 deficiency, along with PAH deficiency, among all HPA patients diagnosed with HPA.

Keywords: Dihydropteridine reductase deficiency, hyperphenylalaninemia, Iran, PAH deficiency, tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency

How to cite this article:

Moradi K, Alibakhshi R, Khatami S. The proportion of tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency and PAH gene deficiency variants among cases with hyperphenyalaninemia in Western Iran. Indian J Hum Genet 2013;19:454-8 |

How to cite this URL:

Moradi K, Alibakhshi R, Khatami S. The proportion of tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency and PAH gene deficiency variants among cases with hyperphenyalaninemia in Western Iran. Indian J Hum Genet [serial online] 2013 [cited 2016 May 24];19:454-8. Available from: http://www.ijhg.com/text.asp?2013/19/4/454/124375 |

Introduction Introduction | |  |

Hyperphenylalaninemia (HPA) comprises a group of inherited diseases characterized by elevation and accumulation of phenylalanine in blood [1] and other tissues [2] (Phe concentration above 120 μmol/l) and if not treated during early infancy, the patients will manifest with impaired cognitive development and function leading to mental retardation. [3] This group of inherited diseases primarily can be caused by a deficiency of phenylalanine hydroxylase (PheOH) enzyme or its essential cofactor, tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). [2] The overall incidence of HPA is around 1 in 10,000 in Caucasian populations. [4] Both groups of HPAs (PAH and BH4 deficient) are heterogeneous disorders varying from severe, e.g. classical phenylketonuria (PKU), to mild forms, according to the plasma phenylalanine concentration prior to treatment onset. [5]

In most of the cases (98% of subjects), HPA results from mutations in the PheOH gene (PAH), encoding the enzyme (PheOH), which converts phenylalanine to tyrosine. [2] Defect in this enzyme is called as PKU or benign hyperphenylalaninemia. [6] The disorder is transmitted in an autosomal recessive pattern and is the most common inborn error of amino acid metabolism in the white population, [7] with the estimation frequency of 1.6 in 10000 in Iran. [8]

BH4 is also a significant cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase and tryptophan hydroxylase (TyrOH and TrpOH), which involved in conversion of tyrosine and tryptophan into catecholamine and serotonin. Due to involving of TyrOH and TrpOH in the synthesis of neurotransmitters, patients lacking BH4 present with progressive neurological disorders due to neurotransmitter deficiency in addition to HPA. [2] Most probably, they are also affected by a depletion of nitric oxide in the central nervous system. Therefore, BH4 deficiency is also known as malignant hyperphenylalaninemia. [9]

BH4 deficiency can be caused by a defect in either the enzymes involved in BH4 biosynthesis (guanosine 5'-triphosphate cyclohydrolase I, [GTPCH] and 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase [PTPS]) or in BH4 regeneration (dihydropteridine reductase [DHPR]; and pterin carbinolamine-4 α-dehydratase [PCD]). The most common cause of BH4 deficiencies is PTPS (approximately 60%) while deficiency of DHPR, GTPCH and PCD represent 32%, 4% and 5% of all cases of BH4 deficiencies, respectively. [10]

Although, according to the literature the overall prevalence of primary HPA due to BH4 deficiency is only 1-2% among cases with HPA, in some countries such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey is higher with the frequencies of 66% and 15%, respectively, because of the high rate of consanguineous marriages within families. [11]

Since the treatment of BH4 deficiency is different from that of PheOH-deficient HPA, a specific differential diagnosis of BH4 deficiency is essential for every newborn or older child with an increased blood phenylalanine concentration. This allows the selection of the correct treatment for the patient. [12]

To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the incidence of BH4 deficiency in Iran. Furthermore, in spite of a previously report regarding the PKU disease among PKU patients of western Iran, [13] there has been no data describing the incidence or prevalence of PKU/HPA in Kermanshah province. Therefore, we designed this study to estimate the BH4/HPA ratio as well as to investigate the different types of HPA in Kermanshah province.

Materials and Methods Materials and Methods | |  |

Patients

A total of 33 unrelated Kurdish HPA patients, born in Kermanshah province, who had been diagnosed in the Imam Reza Hospital (chosen clinic for PKU patients in Kermanshah province) and/or Welfare Organization of Kermanshah, enrolled in our study. These two institutions are the major centers of recording HPA families and assisting them in this province. Patients and their parents were contacted and investigated for this study during 2 years from 2010 to 2011. Detailed questionnaires including informed consent, clinical and family history were collected in the Medical Genetics Laboratory of the Reference Laboratory in Kermanshah. Next, we performed reassessing blood phenylalanine concentrations, not during treatment with a low-phenylalanine diet, by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to confirm patient's HPA as well as exact classifying them to classical PKU, mild PKU or mild HPA (MHPA) with the level of 1200 μM or more; 600-1200 μM and less than 600 μM, respectively. One subject had serum phenylalanine below 120 μM after two tests using HPLC method and was excluded from the study. Consanguinity among parents was proven in 87.5% of remaining 32 patients. The male/female ratio of patients was 1.67 with the median age of 10 years (range 2-23 years). Among the patients, only one of them detected neonatally and the rest born before the Neonatal Screening Program was implemented. Some of the patients were under strict low-phenylalanine dietary treatment, whereas others followed a less stringent vegetarian diet.

Pterins in urine

Oxidized pterins are highly fluorescent and can be detected with specificity and sensitivity after HPLC in urine, blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and amniotic fluid. Although the following tests are recommended for diagnosis of BH4 deficiency variants in the literature; (1) analysis of pterins in urine by HPLC, (2) measurement of DHPR activity in blood from Guthrie card, (3) Loading test with BH4, (4) analysis of pterins, folates and neurotransmitter metabolites in CSF and (5) enzyme activity measurement, here we performed the first strategy in our study. Parallel urine samples (20 ml) were obtained from 32 patients. All the tests were performed within PKU laboratory in Biochemistry Department of Pasteur Institute of Iran, according to Blau et al. protocol. [14]

Results Results | |  |

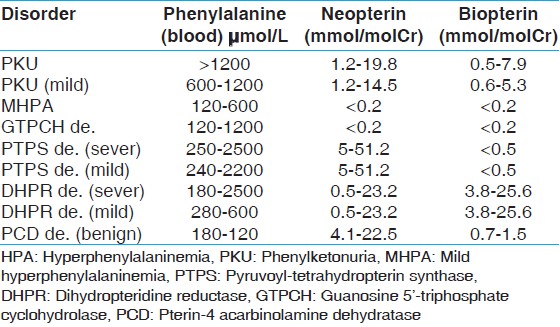

Reassessing blood phenylalanine concentrations of patients enrolled in our study confirmed HPA in 30 cases. One subject was excluded from the study because her serum phenylalanine level was below 120 μM. In addition, pre-treatment blood phenylalanine level was not available for two patients and therefore, their diagnosing as HPA cases had based on the clinical criteria. [Table 1] shows Laboratory parameters (reference values) in patients with various forms of HPA. | Table 1: Reference values of blood phenylalanine and urinary pterins in patients with various forms of HPA

Click here to view |

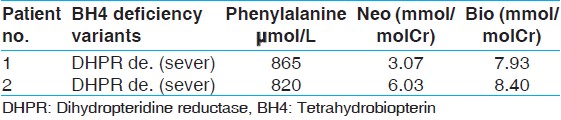

All the 32 HPA cases were screened for BH4 deficiency by urinary pterin analysis. Among them, 30 cases were found with PAH-deficiency (93.5%) and two cases were caused by BH4 deficiency. The BH4/HPA ratio was 6.25% in the HPA population of Kermanshah province. Both of two BH4-deficient patients were assigned to sever variant of DHPR deficiency according to their pre-treatment blood phenylalanine levels, biopterin and neopterin values [Table 2]. | Table 2: Analysis of pterins in urine and cases identified in kermanshah

Click here to view |

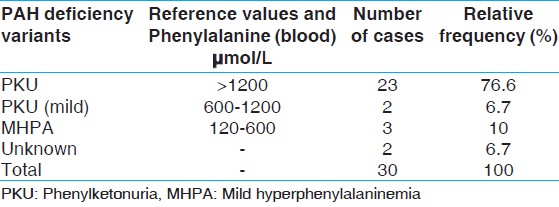

From 30 HPA cases determined as PAH deficiency, 23 patients were classified as classical PKU, two with mild PKU, three with MHPA and two with unknown classification [Table 3]. | Table 3: Classification of patients identified with PAH deficiency in kermanshah

Click here to view |

Discussion Discussion | |  |

Defects either in PheOH or in the production and recycling of its cofactor (BH4) are the causes of primary HPA. PAH deficiency or benign hyperphenylalaninemia is diagnosed based purely on the levels of phenylalanine in the blood. BH4 deficiency or malignant hyperphenylalaninemia is caused by defects in four enzymes involving in biosynthesis or recycling of BH4; GTPCH, PTPS, DHPR, PCD and is diagnosed based on some specially tests, among them analysis of pterins in urine by HPLC. [6] Our purpose has been to identify the variety and the distribution of HPA variants in Kermanshah province population.

Although the limited availability of low-phenylalanine diets and other dietary supplements is still the major problem in Kermanshah, the classification of patients suffered from defects in PheOH into PAH deficiency variants is of particular importance both for treatment and management purposes, based on the identifying of the severity of deficiency. On the other hand, in spite of the fact that the overall prevalence of HPA attributable to BH4 deficiency in Caucasians is only 1-2% of all HPA, differential diagnosis seems to be necessary because not only it's prognosis and treatment is totally different from the PheOH deficiency, but also the severity of BH4 deficiency is higher. [11]

According to our study, on 32 HPA patients from the recorded documents in Imam Reza Hospital and Welfare Organization of Kermanshah province, 30 cases identified as patients with PAH deficiency. On the basis of individual data on pretreatment serum Phe levels, these patients were assigned to one of three arbitrary phenotype categories: 23 (76.6%) had severe PKU, two (6.7%) had mild PKU, three (10%) had MHPA and two (6.7%) had an unknown form of PAH deficiency. Based on these findings and the results of other studies in Iranian population, One can speculate that the pool of sever mutations may be large in this population. On the other hand, it's well known that in milder forms of PKU, e.g., mild HPA, where there is residual enzyme activity, blood Phe concentrations may be only mildly elevated even under conditions of poor treatment diet compliance. Also, it is debated whether those with plasma Phe concentrations consistently below 600 μmol/L (10 mg/dL) require dietary treatment. [15] With regard to these facts and the absence of a systematic newborn screening program in Iran, it's likely that a large proportion of cases with milder forms of PKU, spatially mild HPA, has not been identified and recorded in related centers. Therefore, we think that the frequency of these form of PKU is higher than those was estimated before and/or our findings here.

From 32 HPA patients in our study, two confirmed cases of BH4 deficient patients resulted in an incidence of BH4 deficiency of 6.25% among those with HPA (BH4/HPA ratio), which was higher than the Caucasians. With the using of measurement of pre-treatment blood phenylalanine levels, biopterin and neopterin values, these two cases were diagnosed as sever DHPR deficiency. According to the International Database of BH4 Deficiencies database, deficiency of DHPR represents one-third of all causes of BH4 deficiency. [10] Clinical symptoms of DHPR deficiency are confusingly similar to that of classic PKU and are often misdiagnosed as the classical PKU. However, as already mentioned prognosis is much worse than classical PKU and cannot be solely treated with the PKU regime. Thus, this study would be helpful to the diagnosis, genetic counseling and planning of the dietary and therapeutic strategy in these patients. [12] Furthermore, since the PKU newborn screening program will be available in the near future, our pilot study support that it is crucial to set up screening for BH4 deficiency, along with PAH deficiency, among all HPA patients diagnosed with HPA.

Conclusion Conclusion | |  |

The results obtained indicate a relatively high-frequency of BH4 deficiency in Kermanshah province. Therefore, we can suggest that along with performing comprehensive and intensive studies on HPA incidence in Iranian population, it's better to each province or ethnic region establish its own strategy for a screening program.

Acknowledgements Acknowledgements | |  |

The authors are thankful of the patients for consenting to participate in this study. We also want to specially thank all the people in the Medical Genetics Laboratory at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences for their great collaboration and kindness.

References References | |  |

| 1. | Blau N, Hennermann JB, Langenbeck U, Lichter-Konecki U. Diagnosis, classification, and genetics of phenylketonuria and tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) deficiencies. Mol Genet Metab 2011;104 Suppl: S2-9.

|

| 2. | de Baulny HO, Abadie V, Feillet F, de Parscau L. Management of phenylketonuria and hyperphenylalaninemia. J Nutr 2007;137:1561S-3.

|

| 3. | Surtees R, Blau N. The neurochemistry of phenylketonuria. Eur J Pediatr 2000;159 Suppl 2:S109-13.

|

| 4. | Scriver CR, Kaufman S, Eisensmith RC. The hyperphenylalaninemias. In: Scriver CR, Beauder AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 7 th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995. p. 1015-75.

|

| 5. | Williams RA, Mamotte CD, Burnett JR. Phenylketonuria: An inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism. Clin Biochem Rev 2008;29:31-41.

|

| 6. | Hufton SE, Jennings IG, Cotton RG. Structure and function of the aromatic amino acid hydroxylases. Biochem J 1995;311:353-66.

|

| 7. | Bickel H, Bachmann C, Beckers R, Brandt NJ, Clayton BE, Corrado G, et al. Neonatal mass screening for metabolic disorders. Eur J Pediatr 1981;137:133-9.

|

| 8. | Habib AA, Fallahzadeh MH, Kazeroni H, Ganjkarimi AH. Incidence of phenylketonuria in southern Iran. Iran J Pediatr 2010;35:137-9.

|

| 9. | Blau N, Thony BR, Cotton GH, Hylan KD. Disorders of tetrahydrobiopterin and related biogenic amines. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Childs B, Vogelstein B, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. p. 1725-76.

|

| 10. | Blau N, Thony B. BIOMDB: Database of Mutations Causing BH4 Deficiencies and other PND, 2006 - 2013, Available from:http://www.biopku.org/biomdb.

|

| 11. | Blau N, van Spronsen FJ, Levy HL. Phenylketonuria. Lancet 2010;376:1417-27.

|

| 12. | Jäggi L, Zurflüh MR, Schuler A, Ponzone A, Porta F, Fiori L, et al. Outcome and long-term follow-up of 36 patients with tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency. Mol Genet Metab 2008;93:295-305.

|

| 13. | Moradi K, Alibakhshi R, Ghadiri K, Khatami SR, Galehdari H. Molecular analysis of exons 6 and 7 of phenylalanine hydroxylase gene mutations in Phenylketonuria patients in Western Iran. Indian J Hum Genet 2012;18:290-3.

|

| 14. | Blau N, Duran M, Gibson KM, editors. Laboratory Guide to the Methods in Biochemical Genetics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2011. p. 684-5.

|

| 15. | Mitchell JJ, Trakadis YJ, Scriver CR. Phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency. Genet Med 2011;13:697-707.

|

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3]

|